WHAT IS ORAL LANGUAGE?

We use words and body language to share our thoughts, ideas and experiences with other people; build and maintain relationships; learn new things throughout our lives; to think; and to have our needs met… we’ve all heard the call to action, “Muuummm, I’m hungry!”.

Oral means ‘uttered by the mouth’ or ‘speaking’; so oral language means ‘spoken language‘. Successful communication involves more than just spoken language, though.

As well as knowing and using the words and sentences of a language, communication involves facial expressions, hand gestures, tone of voice, and lots of invisible ‘rules’ about how we interact with others. For example, we don’t usually stare unblinkingly and intensely while chatting; and we take turns in conversations to listen, speak, and ask questions. These invisible social rules are different in each culture of the world, and even differ between different situations within a culture – we behave differently at home than we do at a formal ceremony such as a pōwhiri on the marae.

What has oral language got to do with reading and writing?

Oral language and literacy difficulties can, and often do go hand-in-hand: Almost all struggling readers have some early speech and/or language delays (Adlof & Hogan, 2018). We love the beautiful and powerful phrase; “Reading and writing float on a sea of talk” (James Britton, 1970). Writing is the use of symbols to record spoken language. To read, we must decode these symbols (letters) to turn them back into spoken words, then understand the words using the spoken language networks of our brain. Even when reading silently inside our head, it is like we are listening to an audiobook. To write, we must take our words and sentences from spoken language, and encode them into symbols (letters). Writing is simply spoken language, recorded in symbols on paper.

However, spoken and written language differ in important ways:

Written language contains far more complex words and sentences than we use when speaking. Even picture books for young children contain more unusual words and more complex sentences than adults with university degrees use when speaking to each other! Consider the first sentence of ‘The Hungry Caterpillar’ (Eric Carle): “In the light of the moon a little egg lay on a leaf.’ Or the first sentence of ‘Slinky Malinki’ (Lynley Dodd): ‘Slinky Malinki was blacker than black. A stalking and lurking adventurous cat.’ We don’t tend to speak in sentences like this in everyday conversation, or even at school and work! Through listening to others read to us, and through reading ourselves, we grow our language skills throughout life to know and use extra words and more complicated sentences. Our children need to develop conversational and social language for everyday talk, as well as higher level ‘literate language’ (used in books and writing), and the academic ‘language of learning’ to thrive in school and beyond.

In order to read with understanding, we need strong decoding to lift the words accurately and quickly off the page, AND we need strong oral language skills and background knowledge to understand the words we have read. The well-researched ‘Simple View of Reading’ (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) shows how both aspects are critical to successful reading:

Our brain is primed to process incoming language at conversational speed. If a reader is working very hard to decode (accurately read) the words off the page, the words come in too slowly for the brain to keep them in working memory, and often loses track of the words, making it very hard to understand what has just been read. Children (and adults) can have difficulties in word reading, language comprehension, or both, which causes them challenges with reading and writing.

There is even more going on when writing. To be able to write, we need to:

- plan the writing – organise our ideas into an order that makes sense to the listener or the reader (using oral language)

- select the words from our vocabulary to accurately express our idea

- form sentences that follow the word-order rules of the language

- hold those ideas in working memory while we write the next word and sentence

- retrieve the spelling for the word from memory

- recall the hand movements needed to physically form the letters with our pen (or type them with our fingers) and write letters neatly enough so the writing can be read back later on.

It takes a lot of mental energy (cognitive effort) to do this. Both strong oral language skills and understanding of the alphabetic code used to record words as in writing are required.

Communication Difficulties

Many children experience challenges expressing themselves, understanding spoken language, and communicating successfully with others. This impacts children in many ways. It can affect:

- their learning:

- understanding new information, for example, how fractions work in maths

- understanding and following instructions to complete learning activities, for example, the steps involved in making a kite for Matariki

- building the vocabulary needed for specific subjects – maths, science, history etc

- being able to find the right words and put sentences together to share what they do know by speaking or writing.

- independence:

- growing skills to do things on their own, for example, getting ready for the school day; where to walk to after school for swimming lessons. They need to understand and recall all the steps explained to them.

- social relationships:

- joining in play; keeping up with the rules other kids invent in the games (for example in handball!); starting conversations; understanding humour and telling jokes; building friendships; negotiating; fixing up communication breakdowns and disagreements.

- behaviour:

- may not understand explanations of rules or expected behaviour

- may experience frustration or embarrassment due to difficulties understanding and expressing themselves

- when we don’t understand, it’s very hard to maintain our attention and concentration – we’re likely to end up ‘off-task’.

- emotional development:

- recognising, labelling, expressing and regulating emotions.

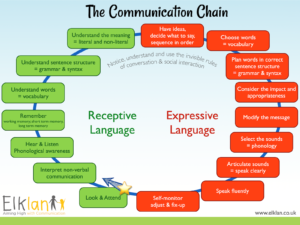

The Communication Chain diagram below breaks down some of the complex elements of speaking, listening, understanding and communicating. It helps us to think about and identify a person’s areas of strength and areas needing support.

The ‘Communication Chain’ diagram is used with kind permission of Elklan Training Ltd, UK.

The components of communication are arranged in a chain to show that a breakdown in any of the links will have effects on the whole chain. A very important link in the chain is the first one – being able to focus attention, maintain attention, and look at a speaker to concentrate on what they are saying. Without this, many of the other steps in successful communication are shaky.

The green side of the Communication Chain shows the processes involved in receptive language – understanding the incoming communication from other people. This is also called comprehension.

The red side of the Communication Chain shows the processes involved in expressing ourselves and getting our message across to others – expressive language.

Something really important to consider is that difficulties understanding communication (all the items on the green side) often go unnoticed – they can be hidden, invisible, and often are only revealed if we carefully go looking for them. If you notice any challenges with attention, behaviour, literacy and learning, check receptive language.

This could be the iceberg under the water and all we can see is the tip above the surface (e.g. behaviour or learning challenges).

Finally, linking the Communication Chain to literacy again:

- If a child can’t understand it, they won’t say it.

- It they don’t say it, they definitely won’t write it.

What do I do now?

There is a lot that can be done at home to help grow children’s oral language and communication skills, see these sites for some quality guidance:

We also recommend the free Progress Checker tools and information on communication development by age produced by ICAN (UK):

- Progress Checker (free, brief tool with questions to identify whether your child may have communication difficulties)

- Universally Speaking – free downloadable booklets detailing communication development from birth to 18 years

If you feel that your child or student may have communication difficulties in any of the areas of the Communication Chain, you can discuss with your child’s teacher, and seek the support of a Speech Language Therapist (SLT). There are SLT’s working in public service through the Ministry of Education (free), and also in private practice (paid services). Significant difficulties in many areas of the Communication Chain may be the result of Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). We know that 50% of children with dyslexia also have Developmental Language Disorder so those children have deficits in both word reading and language comprehension (Adlof & Hogan, 2018). See our DLD information page for more information.

Speech Language Therapists are skilled at assessing all aspects of communication, providing intervention to develop those skills, and working with whānau and schools to help them support the child’s learning, social relationships, and growing independence. More information on Speech Language Therapy services in New Zealand can be found here:

- New Zealand Speech Language Therapists Association (NZSTA) – information for the public

- Ministry of Education – Supporting students with speech, language and communication needs

Thank You

The deb would like to thank Emma Nahna, Literacy Coach, PLD Facilitator, Speech Language Therapist for creating this document on Oral Language for the members of the deb.

References:

Adlof, S. M., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Understanding Dyslexia in the Context of Developmental Language Disorders. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 49(4), 762–773. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_LSHSS-DYSLC-18-0049

McLachlan, H. & Elks, L. (2012). Language Builders. Elklan Training Ltd. St Mabyn, Cornwall, UK. www.elklan.co.uk

This document was created by Emma Nahna, January 2022